The non-singular approach to building a data-driven culture

The past five years have given me a tremendous opportunity to see firsthand data of over eighty VC-backed tech companies. That is close to 100 teams and 300 individuals. Naturally, I’ve got to see a lot of data - very detailed information on every transaction, activity, click, and interaction. What would be expected of me now is to go about promoting for everyone to collect as much information in order to make data driven decisions. Instead, I think all of us in the data profession should be honest about the pitfalls of always championing data-centric approach. Here is why:

- Data is not always right

- Not everyone is naturally comfortable with understanding data

Let’s dive right into it…

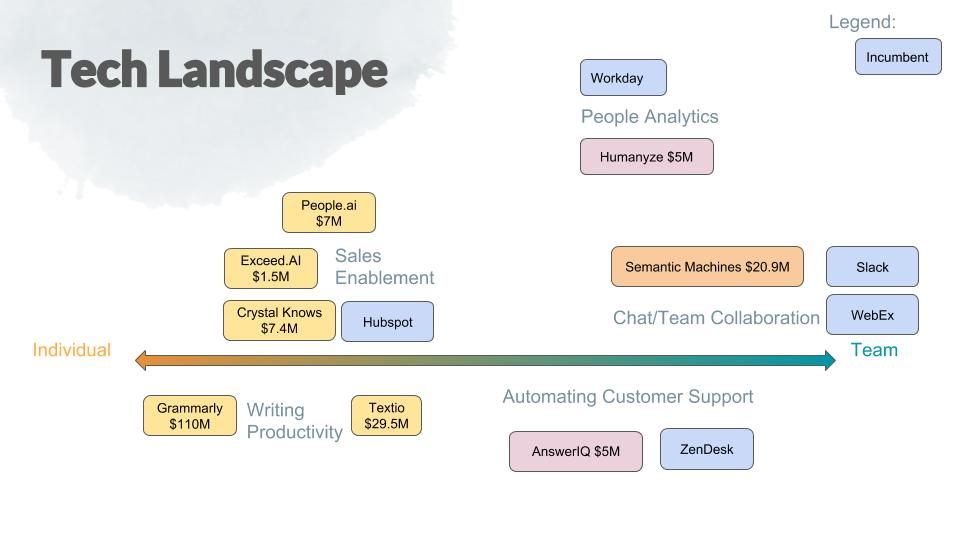

The State of technologies pushing Emotional EQ

If you are non-native English speaker like me, you remember the days when you had to use an online dictionary. You would look up a word, then another — until you translated the whole sentence. This was also the case with translating emails and web pages from other languages into English.

Then, in 2006, Google launched its Translate Service. Suddenly, it was possible to translate whole sentences and even pages. The result was not perfect, but it made online dictionary services obsolete almost overnight. A few dictionary services remained popular for complex languages (Chinese Mandarin, Russian, Hebrew…), and even those are quickly losing relevance.

Twelve years later, there is another revolution brewing in the language space: Interpretation of Emotions. And it is super important! Consider just how interconnected different cultures are today in the digital world. Yes, you can translate email messages word for word, or phrase for phrase, but can you really understand the real opinions and undertones of people behind them? How do you read emotions of someone located far away? How do you tell what someone is feeling if her written or spoken English is not perfect?

What is Emotional …

On growing up in Silicon Valley

For most of the world, Sergey Brin’s story was elevated to myth after Google’s 2004 IPO. By 2008, the Economist had proclaimed Brin to be the “Enlightenment Man” of our era. His ascent after that was the stuff of classic Silicon Valley legend: A visionary drops out of school, spends time in a garage and emerges enlightened. Investors throughout the Valley lined up at his feet to offer patronage. As another Soviet émigré named Sergey at birth, I found myself awestruck when I passed by Brin as he hot-tubbed between diving sessions at Stanford’s swimming pool in 2002. So when in 2005, I too dropped out of college as Brin had, I imagined myself launching the next big thing.

The Future of Work

The world of technology consulting is changing. When I opened my data consulting practice several years ago, I discovered that the model for sales in consulting has changed dramatically over the past decade. Take any sector of IT and there are thousands of software vendors. The world of IT has simply become: too specialized too fragmented too on-demand As a result, traditional sales models, with long sales cycles and scoping conversations, have become inefficient in conveying the value to decision makers across small/medium-sized organizations (and sometimes even enterprise).

On Quality - the Zen of Internet Maintenance

When I talk to friends of my father who have read Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, they all say it had a profound effect on them back in the 1970s. Looking around, sometimes it seems the early tech of the 20th century was built primarily by people influenced by Pirsig’s writing. But it has been more than 40 years since the book was published—where are we now?

When I talk to friends of my father who have read Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, they all say it had a profound effect on them back in the 1970s. Looking around, sometimes it seems the early tech of the 20th century was built primarily by people influenced by Pirsig’s writing. But it has been more than 40 years since the book was published—where are we now?

How to build only meaningful tools

I recently watched a YouTube video of a technical manager from Criteo, Justin Coffey, demoing the in-house business intelligence tool his team had built. It’s a great presentation. Justin actually lists reasons why his team decided to build its own tool; all are good reasons, except none answer why they would have reinvented something when a better tool already exists. (see footnotes) Since I work across vendors and indirectly benefit from the complexity of new data tools—open source included—I also frequently hear reasonable arguments against buying a new tool.

Looker & Google BigQuery Partnerships

[ ]

]

[ ]

]

When my company formalized our partnerships with both Looker and Google, I had a sense that at some point it would be cool to demo some of the work we do with our clients using the two technologies. This, of course, never materialized. As much as our clients wanted to help us, the data was never something they were willing to share.

Why start a Data Consulting Business in 2016?

Recently, I left my best job thus far, the job at Looker, to found a consulting company. Naturally there were a lot of factors at play, but Looker’s gravitational pull on me was due to the technology itself. Looker is one of those technologies that everyone wants to build on top of because:

- It is cool.

- It is permanent.